The Delegate Without a Podium: A Model UN Reflection on Quiet Leadership

Usually, high school students get involved in Model UN their freshman year so they can add it to their college applications — like a resume line.

I didn’t do that.

I joined my senior year, after I had already been accepted to Loyola University Chicago through early admission. Naturally 😆, I thought, “Now seems like the right time to get involved in school activities.”

But I couldn’t help it — I had this itch to join the Model United Nations club. It had been quietly calling my name for years, and I finally had the courage to go for it senior year and break away from the “cool kid” orbit I’d been circling.

So, the first week of senior year, I walked into a classroom for their first after-school meeting — flyer in hand — and had to double-check that I had the right room. You could have heard a pin drop. Conversations stopped, and every face turned toward me in the doorway.

“Hi everyone. Is this Model UN? I’d love to sign up!”

The surprised looks

melted into smiles, and they welcomed me with open arms — thrilled to have me.

I was officially sworn in as the club’s oldest newbie: a wide-eyed 18-year-old

joining a crew of seasoned underclassmen.

Looking back all these years later, I’ll tell you: stepping into the club senior year without the benefit of three years of practice was actually a blessing. I came in with fresh eyes. And I was a natural at diplomacy and reading people.

Here’s what Model UN is: students are each assigned a country and given a global issue to solve — like a refugee crisis. You have to represent your assigned country’s policies, even if you don’t personally agree. You engage in formal debate, write policy resolutions, form alliances, negotiate, and speak persuasively. You research, compromise, and sometimes outmaneuver opponents — all through diplomacy.

Most students were laser-focused on crafting their own resolutions, hoping to win based on the strength of their individual ideas. They’d rush to the podium to pitch their country's position and miss the bigger picture entirely: every other delegate in the room wanted their own proposal to win, too.

I was the new senior in the room — just happy to be along for the ride — watching these passionate younger students in action. And I saw potential in the scattered proposals around me.

So I started calling for recesses, quietly pulling delegates together — side huddles, small group chats. With a friendly smile, I’d ask questions like the curious newcomer I was:

“What do you think? Could these ideas work together?”

Those are deferential questions — questions that show respect and genuine curiosity. And people like that, no matter their age. It disarms them. It puts them into a positive, creative state of mind where brainstorming begins — and that’s exactly what you want in any situation.

When people realize you’re not trying to compete with them, they lower their guard. They start opening up, sharing ideas, and offering feedback — the kind of feedback you can use to refine and align.

I surprised them. I wasn’t there to compete. I wasn’t chasing points. I was just having fun — and seeing how we might bring different proposals into harmony.

I was in my element — inspired by their energy, helping these younger rising stars do something meaningful together.

I helped them merge proposals, cut the parts that clashed, and build consensus.

I listened.

I refined.

I helped people feel heard.

And by the time they presented their joint resolutions to the full assembly, they had built something they all had a role in shaping — and it almost always passed, with the most countries co-sponsoring.

That was me.

That was my gift.

I’m a born peacemaker. An inspirer. I bring people together.

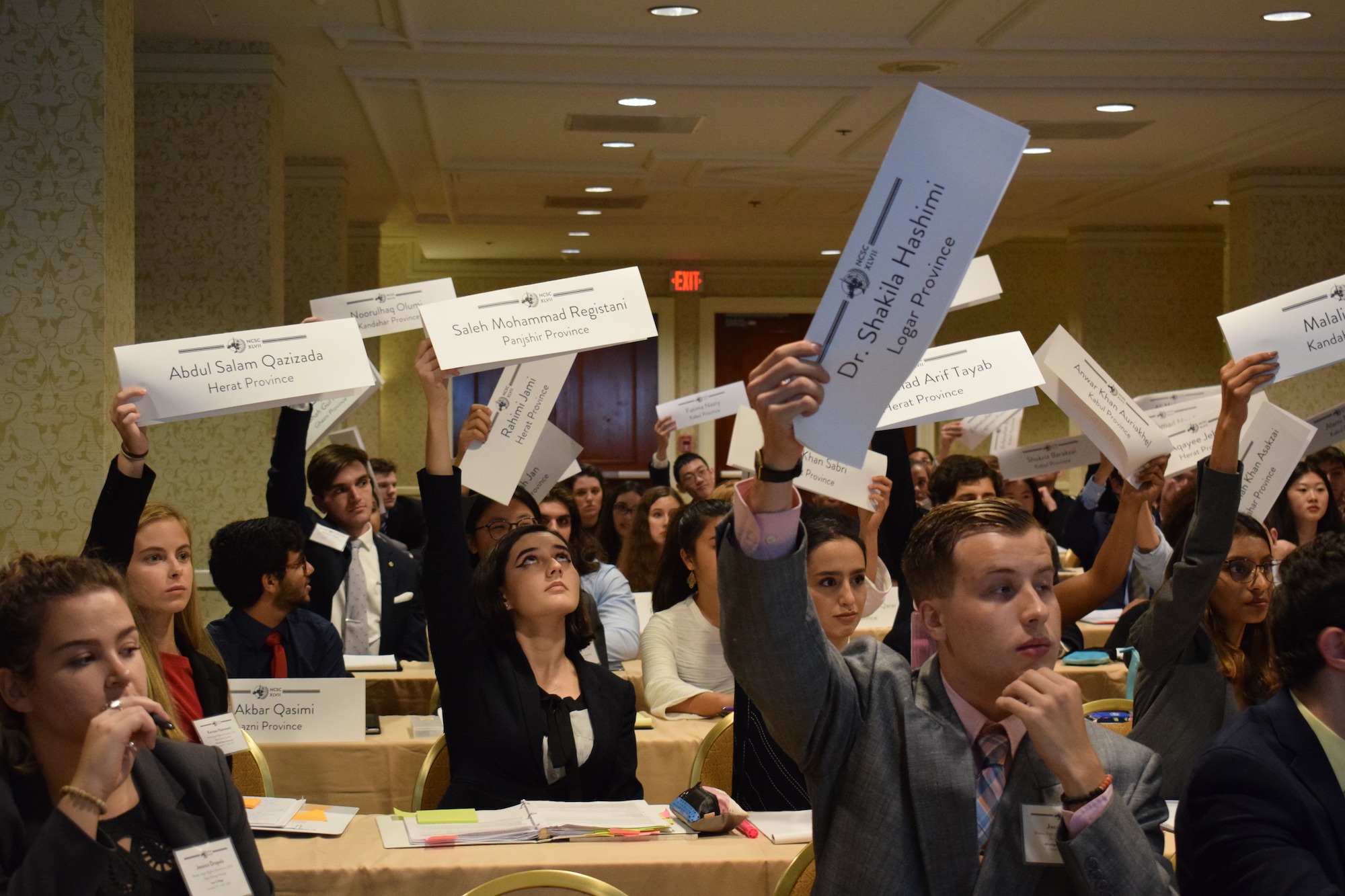

Later that year, I competed in my first national Model UN conference at Georgetown University, going up against thousands of students from some of the most elite prep and boarding schools on the East Coast — students who would go on to become lawyers, U.S. representatives, and government officials.

So when my name was called during the closing ceremony for the Outstanding Speaker Award, I was stunned.

It was a Rudy at Notre Dame moment.

I was so caught off guard, my classmates from our Midwest high school had to tap me on the shoulder to tell me to stand up and accept the award. I whispered, “Wait — what even is that award?”

The moderators had been watching during the session breaks — all the quiet recesses I had called, the side huddles I pulled together, the proposals I helped merge behind the scenes in the hallway of the General Assembly. I’d been doing what I’d always done in our local sessions: facilitating, aligning, translating between delegates.

It was a public acknowledgment of a timeless truth I’ve always known:

Behind-the-scenes leadership can move a room more powerfully than a podium.

Post a comment